Big O, is a mathematical notation use in computer science to describe the behaviour of an algorithm. Usually either space (its memory footprint while running) or time complexity.

Why Big O notation

The Big O we’ll be looking at is a simplified version, and how to quickly calculate it. It is something you can enjoy mastering, if you need to build particularly efficient algorithm. But for most of the people, we just need a general idea of how slow our algorithm.

Big O notation is really useful when you know you’ll have a tone of data to process, then you’ll be interested to have an algorithm that performs well on average and not too bad at worst.

The time or space complexity matters depending on the likelihood of operations. The more operation will be performed, the more time or memory it will take, which will either slow down your program or make it crash. So it’s not about optimising at all costs, but optimise where it matters and knowing the strength and weakness of your algorithm.

The simplified version

Or basically how to read it. You may have seen \(\Omega\), \(O\) and \(\Theta\) in terms of algorithm time complexity. Basically:

- \(\Omega\) is the time for best case,

- \(O\) for the worst case

- \(\Theta\) is basically of both \(\Omega\) and \(O\) notation

Nowadays, Big O is mostly used to describe as tightly as possible the algorithm.

There’s an infinite number of Big O notations, and you need to understand the concept to grasp it fully. However, there are some notations that you’ll see more often than others. Here is what to consider:

- \(1\) usually means it’s a constant time

- \(N\) in the notation usually means the number of elements (like in an array)

- We consider the notation in terms of “power” (\(2N\) is considered equal as \(N\) but is faster than \({N}^{2}\) and slower than \({\mathrm{log}}\left(N\right)\))

- Any other letter, means there are two operations with different size (like on will be \(A\), and the other \(B\))

So let’s review the main ones.

Examples

Looking at the main time complexity in those examples.

Constant Time

For a constant time \(O({1})\):

fun constantTime() {

repeat(100000) {

print("Big O(1)")

}

}

Sure doing that 100000 times is a bit long and tedious, but the constantTime() function will always execute it the same way.

For example, accessing an element (array[0]) in an array is a constant time operation \(O(1)\),

because it doesn’t matter how big the array is, the memory address of the array’s element can be calculated directly.

However, looking for an element in an array (array.contains(element)) is a linear time operation \(O(n)\),

because you need to go through the array to find it.

Linear Time

For a \(O({n})\) time:

fun notConstantTime(n: Int) {

repeat(n) {

print("Big O")

}

}

This time you can see that notConstantTime(n) execution time will vary depending on n.

If there are too loops one after the other that go through \(n\) then \(m\) elements, the time complexity is \(O(n+m)\).

(0..n).forEach{ i -> print("Big O - [$i]") }

(0..m).forEach{ j-> print("Big O - [$j]") }

The difference between \(O(n)\) and \(O(n+m)\) is good to know, but it could still be considered in the range of \(O(n)\), with the idea that the time complexity is not that notable.

Polynomial time

For \(O({n}^{2})\) time:

fun squareTime(n: Int) {

for (i in 0..n) {

for(j in 0..n) {

print("Big O - [$i, $j]")

}

}

}

So basically you go through a range that goes from 0 to n, and each time you go through the same range from 0 to n.

In the end squareTime(n) execution time will be n times n.

Then we have two cases from this one:

- With an array of size \(n\) and an array of size \(10000\). Then the time complexity stays \(O(n)\) because we drop constants

(0..n).forEach{ i -> (0..10000).forEach{ j-> print("Big O - [$i, $j]")}}

- With two arrays of size \(a\) and \(b\), the time complexity is \(O(ab)\) because \(a\) and \(b\) are different.

(0..a).forEach{ i -> (0..b).forEach{ j-> print("Big O - [$i, $j]")}}

Logarithmic time

For \(O({\mathrm{log}}\left(n\right))\) time:

fun logTime(n: Int) {

while (n >= 2) {

println("Big O - [$n]")

n /= 2

}

}

So this one is logarithmic, because each time you do an iteration n is divided by two. It is logarithmic on base 2, for example:

- If \(n = 8\), then there will be \(3\) iteration.

- And we have \({\mathrm{log}}_{2}\left(8\right)=3\) because \({2}^{3}=8\)

For the logarithmic time, so if you have two loops, with the first one going through \(n\) elements and the second inner loop going through \(n/2\) elements (skipping elements), then the time complexity is \(O(n{\mathrm{log}}\left(n\right))\) and not \(O(n^{2})\).

(0..n).forEach{ i -> (0..n/2).forEach{ j-> print("Big O - [$i, $j]")}}

The time complexity between \(O(n{\mathrm{log}}\left(n\right))\) and \(O(n^{2})\) can be quite notable!

To go further

Basically, to find the good \(O\) notation, you need to pay attention to three things mostly:

- The number of loops (multiplying inner loops)

- The size of the data (is it one size \(n\), multiple size \(a\), \(b\), …)

- How you go through the data (is it a fixed amount of loop, or does it change like for the logarithmic time example)

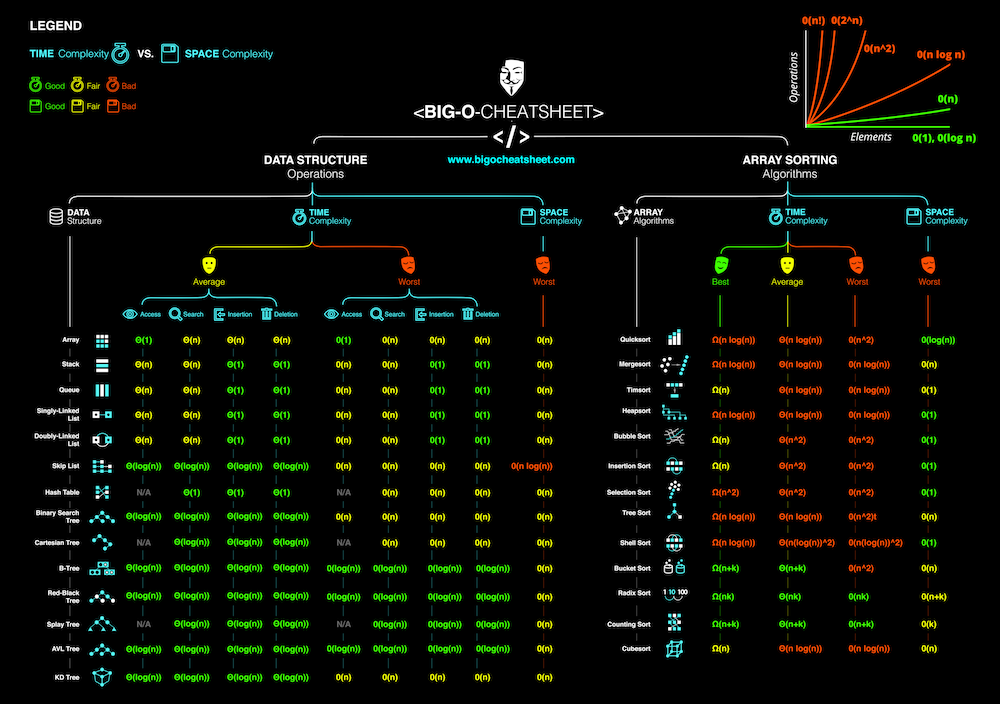

Also find the bigO cheat sheet online for an easy reminder when choosing your data structure.

This will help you improve your algorithm, and if you want to know even more, there are lots of examples out there and tones of good explanations.

On the cheat sheet, it shows for common data structure the time complexity scenarios for the access, search, insert and delete operations. What’s important is the time complexity is given for the average case and worst case scenario depending on the inputs. For the space complexity, it’s always looking at the worst case (with \(n\) elements in the data structure).

On the right, it’s the same principle but for some common sorting algorithm, with the best, average and worst possible time complexity as well as the space complexity for each algorithm.